To celebrate National Science Week 2024, we hosted Camera Trap Chronicles, a photo exhibition in Launceston and Hobart that showcased images submitted by WildTracker citizen scientists, landholders, and researchers from across Tasmania.

Each photo was accompanied by a personal story from the entrant, sharing their connection to the animal, alongside a panel offering scientific insights into the species and behaviours depicted. We’ve now digitised the exhibition for you to explore. The winning photos from each theme — Behaviour, Comedy, Threatened Species, Firsts, and Research — are below.

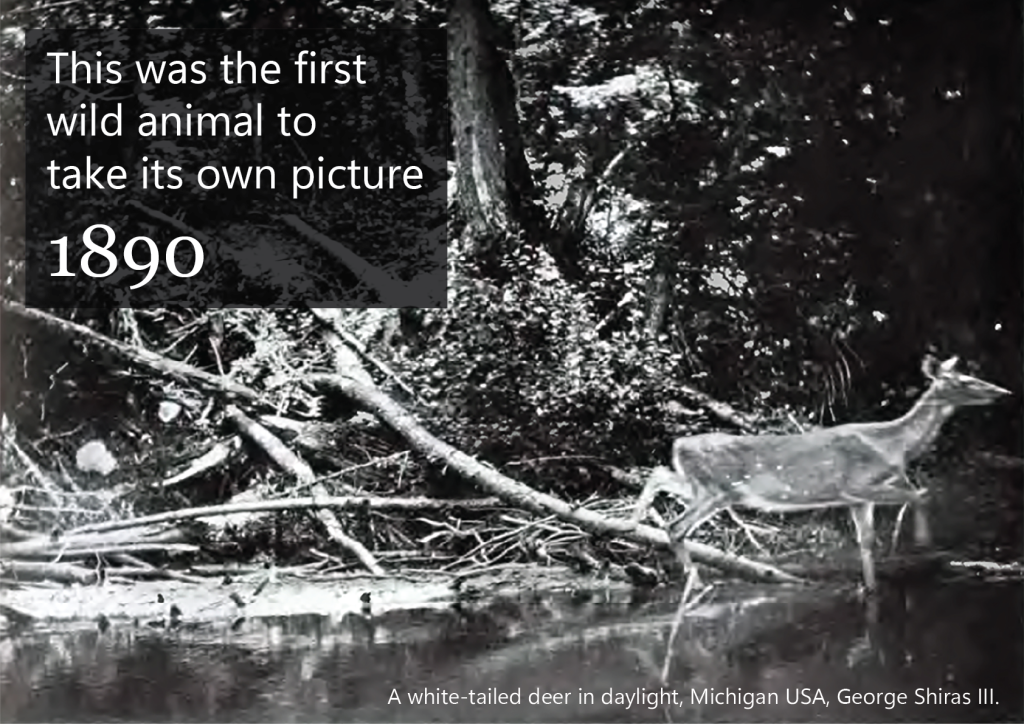

Lying beside a blazing camp fire that accentuates the darkness of the night, the sportsman may suddenly see a dazzling column of light on a distant hillside, or above the gloomy valley of some water course. The deep, dull boom of the exploding magnesium powder a few seconds later raises a mental vision of an animal fleeing in needless terror from a bulletless weapon and leaving a record of its visit that will give pleasure to one who means it no harm.

GEORGE SHIRAS 3RD “Father of wildlife photography” Hunting Wild Life With Camera and Flashlight 1929, National Geographic Society, Washington USA.

People’s Choice

Mum’s home, sweetheart

Mum had two spots to sleep after foraging, and this one was in the sun right outside the burrow. When she came home from a few hours foraging, bubs couldn’t wait to play, but mum wasn’t having it. After a few attempts to wake her up, bubs gave up, climbed up into the sun, and had a wee nap on mum’s back! These photos were collected on our Land for Wildlife property.

Ben and Brenda Marshall

Bare-nosed wombat (Vombatus ursinus)

Tasmania is home to two of the three subspecies of bare-nosed wombat; V. u. tasmaniensis occurs on mainland Tasmania and V. u. ursinus is now restricted to Flinders Island and Maria Island where they were translocated in the 1970s (extinct on King). Tasmanian wombats are smaller than their mainland counterparts. But did you know that GIANT wombats once roamed the Australian continent? Phascolonus gigas weighed between 100 and 250 kg and lived as recently as ~40,000 years ago. Wombats can breed at any time of year. Joeys leave the pouch when they are around six months old and weigh approximately three kilograms, but they only leave their mother’s watchful eye at about 18 months. While wombats often appear lackadaisical or snoozy, like the ones in this photo, they can reach an incredible top speed of 40km per hour if needed.

Threatened Species

Quollity time between siblings

A pair of juvenile quolls spent a few days playing around this burrow next to the driveway. The camera took both still photos and videos of interactions between this adorable pair. One of the quolls has a distinctive mark on its left side, like a sideways 8, which made it easy for me to identify. This one was captured on camera travelling all over the property for the next ten months.

Larena woodmore

Spotted-tailed quoll (Dasyurus maculatus)

The Tasmanian population of spotted-tailed quolls, sometimes called the tiger quoll, is currently listed as Vulnerable under federal legislation. The species maintains low densities across the state except for the Bass Strait Islands where they have sadly become extinct. Historically, spotted-tailed quolls were present along the Great Dividing Range on the mainland, stretching from northern Queensland to Victoria and southeastern South Australia. Their range is now fragmented with Tasmania being an

important stronghold for the species.

Spotted-tailed quolls are mostly nocturnal creatures. During the day they den in tree hollows, using their adept climbing skills, as well as in underground burrows, small caves, in thickets of vegetation like gorse, and among rocks and coarse woody debris. Their breeding season spans from June to July, with pouch young potentially observed from July to September. Young quolls reach independence at around five months old, with an average lifespan ranging between three and four years.

Comedy

Stick ’em up!

Having a wildlife camera is almost a must when you have curious possums around! The brushtail possums are not just adorable, they are endlessly entertaining as they approach the camera, sniffing and pawing at it with genuine curiosity. They are always up to something! These two are mum and daughter I believe. They are very close, but sometimes the teenager likes to challenge mum.

Elleke Leurs

Brushtail possum (Trichosurus vulpecula)

Threat displays are behaviours animals use to signal aggression or dominance without engaging in physical conflict. They may stand on their hind legs, puff up their fur or feathers, and adopt postures that make them look larger or more formidable. The goal is to intimidate the opponent and avoid a costly fight in terms of energy and risk of injury. Brushies establish dominance hierarchies in both wild and captive populations. Females are generally dominant over males, but within each sex, dominance is related to age and body size. A possum standing upright with its arms in front of its chest is in an “alert posture.” A bipedal stance with forelegs raised indicates readiness to strike, known as the “bipedal threat” posture. Possums might also give a guttural hiss or high screech, depending on the display’s intensity. Although it may appear offensive, this is a defensive posture that can be shown by both dominant and subordinate possums of any sex when another approaches. It need not result in an attack or chase.

Firsts

Devil Dash

Whilst still mastering the art of setting up a camera trap that was not triggered one million times by the ‘wind’, I was first stoked with the camera proving that devils did indeed reside on our property, despite not having seen one in seven years of living here. Then I managed to capture these photos and was elated to know that baby devils were about!

Carolyn Asman

Tasmanian devil (Sarcophilus harrisii)

Like other marsupials, devils give birth to tiny ‘neonates’ (six millimetre jelly beans) that scramble to the pouch, where they suckle for about 100 days. Up to four young leave the pouch in Spring or early Summer. The joeys in this photo are quite large to still be hangers-on, especially so late in the season. It is likely that a devil den is located near the camera site. With the spread of DFTD, females typically only have one breeding opportunity in their lifetime, leading to a younger age at reproduction. The overall age structure of devil populations has shifted, with most devils not surviving beyond three years — a significant decrease from the pre-DFTD lifespan of five or six years. Male devils, much like other dasyurids (Greek: hairy tail), invest heavily in reproduction at the expense of their own longevity. They may lose up to 25% of their body weight, become anemic, and have reduced immunity during the mating season.

Behaviour

Currawong hide & seek

This photo was taken on a dirt track on our property up near Brady’s Lake in the Central Highlands. We have many Currawongs, mostly by themselves or in pairs. Here they all come together, sort of.

Matt and Kim Jose

Black Currawong (Strepera fuliginosa)

Outside of the breeding season, individuals of many bird species flock together. Sometimes birds of different species even team up for the winter. But why? The “dilution” and “many eyes” effects explain how safety is found in numbers. Not only does being in a large group reduce the likelihood of any one individual being targeted by a predator, but it also boosts overall vigilance. By sharing the responsibility of keeping watch, individuals can forage more efficiently. Black currawongs congregate in large flocks, usually ranging from 20 to 80 birds, but sometimes numbering in the hundreds. In these groups, currawongs can more effectively locate and share information about food resources. They are also better able to defend their territories and mob any intruding predators. Young currawongs gain invaluable experience bu flocking, as they observe and interact with adult members, learning essential survival skills.

Research

Times like this I wish I were a hairy-nosed

wombatBare-nosed wombat (Vombatus ursinus)

This wombat was out during daylight in winter near Lake Augusta on the Central Plateau. Wombats are abundant in this area and they need to dig through the snow to reach their food.

Department of Natural Resources Tasmania